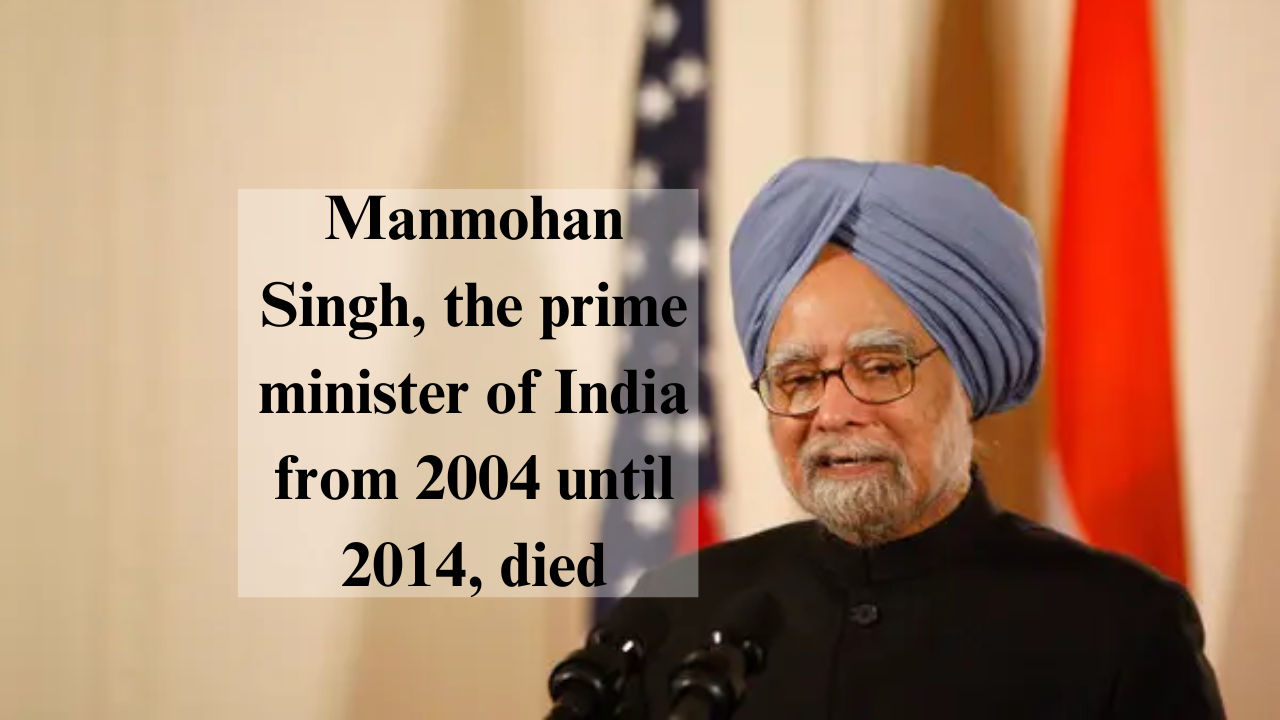

Manmohan Singh, 92, died in New Delhi on Thursday. Singh was the first Sikh, a minority religion in India, to hold the position of prime minister. Despite being a well-known economist and the pioneer of economic changes in India, he was viewed as a weak leader by many, including some members of his own party, the Indian National Congress.

“India mourns the loss of one of its most distinguished leaders, Dr. Manmohan Singh Ji,” Prime Minister Narendra Modi said on X. He rose from humble beginnings to become a renowned economist. As our prime minister, he put a lot of effort into improving people’s lives.

Singh’s time as finance minister in the early 1990s, according to political experts, was more significant than his time as prime minister from 2004 to 2014. At the time, his policies set India on the path to economic liberalization and globalization.

As former U.S. President Barack Obama wrote in his memoir A Promised Land, Singh was “smart, considerate, and scrupulously honest.”

Singh was born in the modern-day Pakistani village of Gah on September 26, 1932. His family relocated to the east after Great Britain divided the subcontinent in 1947 into independent India and Pakistan, a predominantly Muslim nation. The division caused enormous migration and sectarian violence that killed hundreds of thousands of people, including Singh’s grandfather.

Singh, an Oxford-educated economist, opened up India to the free market in 1991 with one of the most radical budgets in Indian history.

“Make it clear to all people worldwide. Singh said in his budget speech that “India is now wide awake.”

Finance and public policy expert Rajesh Chakrabarti claims that “the budget declaration was a shocker because it nearly turned on its head most of what was the received economic wisdom of the day.”

Chakrabarti claims that up until 1991, India’s economy was socialist, governed by the public sector, and subject to import restrictions. When Singh was named finance minister, the situation was dire. India was having severe problems with its balance of payments.

“We were importing far, far more than what we were exporting, and our foreign exchange reserves had touched a low,” says Chakrabarti. “India had to actually ship out gold — that means physically putting its gold reserves in ships and sending them to [banks in] London, to get money for running the economy.”

Singh’s historic budget lowered import duties, opened India’s economy to foreign direct investment, and abolished the Permit Raj, a complex system of regulations and red tape that discouraged private investment.

When Sonia Gandhi, the matriarch of the Congress party and an Italian by birth, rejected to become prime minister following the party’s overwhelming victory in 2004, Singh was thrust into the public front once more.

But critics called him the Gandhis’ “puppet,” ridiculed his taciturn manner, and said he was not a persuasive speaker.

According to Rasheed Kidwai, who wrote a book about the Congress party, his inability to perform for the audience made humility both a strength and, to some extent, a weakness.

However, Kidwai asserts that he guided India through several domestic and international issues.

“India stood firmly when the world economy tottered in 2008,” he said. While Singh was in office, “there was no confrontation with difficult neighbors like Pakistan and China,” despite the 2008 Mumbai terrorist attack by Pakistani militants.

Kidwai said Singh was highly successful in international policy. He says, “He was not one-dimensional,” “[Singh] had very good relations and functional ties with Iran, and at the same time he was highly welcomed in Saudi Arabia.”

Under Singh’s leadership, India took a number of steps toward closer relations with the US. It is noteworthy that the two countries agreed to lift a decades-old prohibition on nuclear commerce. Singh also launched a social welfare program that boosted India’s economy and guaranteed jobs in rural areas.

But his second tenure was marred by accusations of corruption, and in the 2014 national elections, his Congress party suffered its worst-ever defeat.

Singh chose not to run for office again after the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party easily won those elections. He was exonerated of any responsibility in the corruption-related scandals.

After Singh quit his work, Manmohan Singh and his family stayed in Delhi. He is survived by his wife, Gursharan Kaur, a historian, and their three daughters.

Chakrabarti said Singh was one of India’s most graceful prime ministers. “I don’t think even his worst critics will ever have anything but respect for the man,” he says.

Singh said, “My life and tenure in public office are an open book,” during his goodbye speech in 2014. He was wearing his signature light-blue Sikh turban at the time. “I’ve had the privilege of serving our nation. I can’t possibly ask for anything more.”